Buying the power

Striking a raw nerve

Were civil servants right to threaten to strike to strong-arm government to approve salary increases? Did the unions sell out the majority of civil servants? How will government foot the increased wage bill? Business7 spoke to experts across the board.

The N$924-million wage package increase for government employees might burn a hole in the state coffers, but it will not patch the hole in the pockets of the majority of civil servants.A plunge of nearly 25% in the buying power of civil servants since 2016 recently forced an overwhelming 97% of union members – or 42 216 workers in the bargaining units - to vote in favour of a nationwide strike. They demanded a basic salary increase of 5%, a 9% increase in housing allowance, a 10% rise in transport and vehicle allowances, and N$7 per kilometre travelled.

Government last week pacified the unions with an offer which includes a basic salary increase of maximum 3% across the board.

It worked.

The general secretary of the Namibia Public Workers Union (Napwu), Petrus Nevonga, and the general secretary of the Namibia Teachers Union (Nantu), Loide Shaanika, signed government’s offer agreement on 4 August.

NO CUSHION

Civil servants last received a salary increase in 2016. N$1 000 in January 2016 is worth about N$753 today in terms of purchasing power. Their buying power, like the rest of Namibian consumers, has thus eroded by nearly 25%, experts told Business7.

The deal between the government, Napwu and Nantu “won't cushion civil servants at all against the vagrancies of cost of living crisis”, Dr Omu Kakujaha-Matundu, a senior lecturer in economics at the University of Namibia (Unam), said.

“For those in lower salary brackets it is not an improvement at all. Even those in the middle-salary bracket won't be able to afford to service their mortgages as we are moving into high interest rate environment,” Kakujaha-Matundu added.

The deal between government and the unions also includes an increase of 11% in housing allowances for all civil servants below management, as well as 14% more in transport allowances, excluding management. The total offer was backdated to 1 April this year.

‘PRIVILEGING THE PRIVILEGED’

Prof Henning Melber described the union demands as “class based”, saying it was not in favour of the most needy and those at the bottom of the social ladder.

“The demands for a pay rise across the board is simply turning trade union demands into an elite project,” he said, adding: “The increase of salaries across the board privilege the privileged and enlarge the inequalities. Namibia needs the opposite to secure sustainable development and lasting stability.”

Namibian-born Melber is an associate the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI) in Uppsala, Sweden. He is also an extraordinary professor at the University of Pretoria and the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein, as well as a senior research fellow at the Institute for Commonwealth Studies/School for Advanced Study, University of London.

Melber said the unions’ deal with government “will not only reproduce but deepen the inequalities in income”. Since inflation hurts the poor and those with little income most, demands should have been on a scale, he added.

According to Melber, civil servants who earn the lowest salaries, like cleaners and other manual labour workers, should have received an increase of about 10%, as they “hardly manage to make end meets any longer”.

Government’s middle-income earners like teachers, nurses and other relevant social services groups should have received “at least a minimum increase of 5%”.

FREEZING THE TOP

Management in the civil service shouldn’t have qualified for higher salaries and fringe benefits, Melber said.

“After all, those in the higher civil service have been very well paid and can afford a factual reduction of income (which no increase means under the current inflation),” he added.

Melber continued: “They would of course complain and feel discriminated. But given the bloated civil service, in particular on higher levels, they can of course resign and move on - only that they might find it difficult to secure something else in a similar category of income.”

BLOATED BURDEN

Government employed an estimated 108 421 people at the end of March this year, according to the latest government wage index of the Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA).

Cirrus Capital economist Robert McGregor said given the increase in food and fuel prices since the last wage adjustment of civil servants, demands for an increase and the strong support for the strike came as no surprise.

Labour researcher Herbert Jauch said the decision to strike was justified due to the many years without salary increases.

“After lengthy negotiations, they were faced with a scenario of minimal adjustments, way below the current inflation rate. After exhausting all other avenues, the strike was the only route left and thus the threat of the right to strike was the only option,” he said.

LENGTHY BATTLE

The unions have been fighting for increases since February last year.

Government initially said it couldn’t afford any salary increases, but agreed to a 14.5 % increase in housing allowances for staff below management and 12% for employees in managerial positions. The unions rejected it.

Government then upped its offer to a total of about N$334.9 million. This comprised of a 7% increase on the homeowners scheme for staff members, an increase on the housing benefit for non-management workers to 14.5%, an increased housing benefit for management to 12%, and a transport benefit increase for non-managers to 14%.

This too was rejected by Napwu and Nantu, forcing government to increase the settlement offer to just short of N$1 billion.

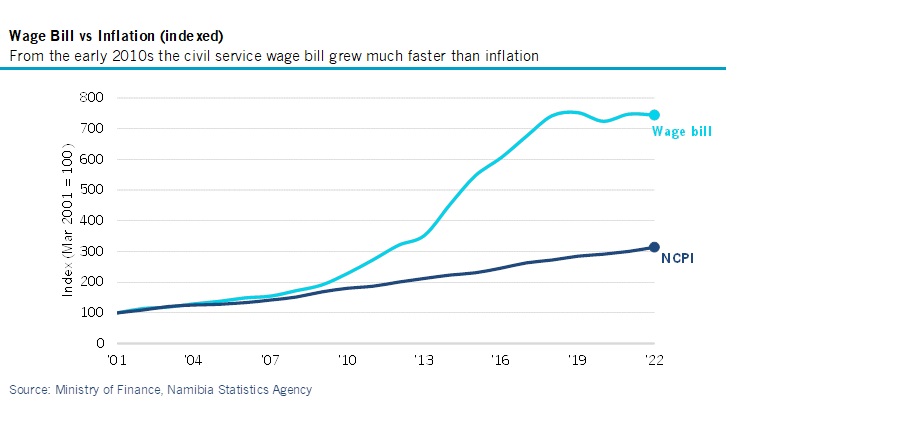

Commenting on the wage issue, McGregor said it must be borne in mind that in the early 2010s the civil service was increased in size and underwent a regrading exercise that saw wages increased.

“Thus, while price levels rose 1.7 times from March 2001 to March 2018, the civil service wage bill increased 6.4 times over the same period. Additionally, unlike many in the private sector, civil servants did not see retrenchments or wage reductions at any point during the pandemic.”

BULGING BULGE

The agreed wage settlement will push government’s total wage bill in 2022/23 up to more than N$31 billion – nearly 44% of total operational spending and about six times more than the total development budget in the current fiscal year. It will also slurp up more than half of the total estimated revenue government expects in 2022/23.

The size of Namibia’s civil service and its wage bill has been a bone of contention for years. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), as well as credit rating agencies Moody’s and Fitch have stressed their concern about the mounting costs repeatedly.

Government embarked on its fiscal consolidation stance in 2016 in order to regain fiscal and macro-economic stability. This included freezing non-critical posts, stagnant salaries and wage bill reform intentions.

Commenting on the new wage bill increases, McGregor said government must be commended for its ability to hold off on wage adjustments for such a long time.

“Government’s stance on limiting wage adjustments is fiscally prudent, given that we have run deficits over the past decade and will continue to run deficits over the medium term,” he said.

For the last nine years government’s personnel expenditure has been more than double the revenue received from personal income tax collection, he added.

FOOT THE BILL

Government will either need to redirect spending from other parts of the budget, or increase its deficit and raise additional debt, or some combination of the two, according to McGregor.

“Over the last eight years we have seen many instances of re-prioritisation within the budget, largely development expenditure being reduced to favour operational expenditure (such as the wage bill).

“This is not sustainable, particularly given the poor state of much infrastructure that should form the core activities of any government (education, healthcare). Given that previous budget statements have suggested there is little other fat to trim for the wage bill, it is difficult to see where else this could come from,” he said.

Simonis Storm (SS) economist Theo Klein agrees.

“We might see certain sacrifices on other services or priorities that form part of government’s expenditure bill. This could potentially also lead to lower budget allocations to state institutions which could further hamper on their activities, effectiveness and services which they provide to society and the economy.

“An example might be that the Namibian Statistics Agency does not receive sufficient funding to conduct a population census. As a result, government might have to increase other sources of revenue (such as increasing tax rates) or borrow more from local or foreign investors to pay its bills,” Klein said.

BORROW TROUBLE

Increasing the deficit to fund the wage bill increase is also not without concern, McGregor said.

“Issuing more debt in a rising interest rate environment will increase the marginal cost of funding, where interest payments are already worryingly high. Additionally, this would add to an already large deficit, an increase of N$924 million to this year’s borrowing plan (whether domestic or foreign) would see some market participants react disapprovingly,” he said.

Klein commented that government bonds in primary auctions have seen healthy levels of demand, particularly in the second quarter this year. “So, it should not necessarily be too difficult for government to raise the necessary capital from the local market to fund the salary increases,” he said.

However, he added: “This is not an ideal solution as debt raised from local investors should rather be funding developmental spend in the economy (e.g. infrastructure, housing, schools, etc.) and not financing operational expenses. However at the same time, this is better than government raising tax rates to raise the necessary money to finance the salary increase.”

McGregor’s closing thoughts were: “While the unions are looking out for the interests of their members, these are not without costs for the country as a whole as fiscal sustainability is a material concern. Raising additional debt to fund operational expenditure is simply unsustainable.”